MAY 2023

THE

NOTORIOUS

AND TRUE

HISTORY OF

NYC’S FINEST

POLICE REFORM ORGANIZING PROJECT

ABOUT

The Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP) is a non-profit, tax exempt organization that uses policy analysis & advocacy, research & public education, as well as community organizing to expose and end the abusive and discriminatory practices of the NYPD.

In addition, PROP advocates for directing the money saved to services & programs that help rather hurt & punish New Yorkers, especially the New Yorkers who endure the brunt of unjust & abusive law enforcement policies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The principal authors of The Notorious And True History Of New York's Finest are Sophia Davis and Evan Karl who prepared the substantive draft of the report while working as interns with PROP during the summer of 2022.

Without their dedicated and impressive efforts we would not have been able to produce this history. Its main editor is Robert Gangi who received significant feedback and assistance from Antony Ward, Luke Messina, Josmar Trujillo, Urooj Rahman, and Isabella Lucia Maitino. Ms. Maitino also did invaluable work in providing and finalizing the document's many citations.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The “Kidnapping Club” and the Treatment of Black Residents

Policing During The Civil War: Draft Riots and Racial Resentment in an Era of Economic Downturn

NYPD Corruption and the Lexow Committee

Policing at the Turn of the 20th Century

NYPD’s Persecution of New York City’s Queer Community

Stock Market Crash and the Harlem Riot of 1935

Harlem and Bed-Stuy Riots of 1964

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

As its title reflects, The Notorious and True History of NY's Finest focuses on presenting the NYPD's all too often notorious practices over the course of two centuries dating back to its founding in 1845 and the actions of its historical precursors. These harmful policies most frequently took the form of targeting and victimizing low-income NYers of color. Here's a list of some disturbing incidents presented briefly here and documented at greater length in the full report:

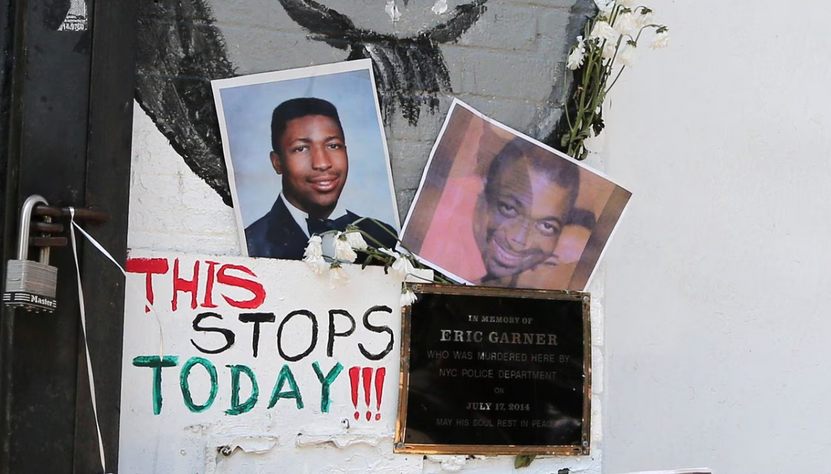

The NYPD killing of Black men -- These fatalities included John Derrick in 1950; 15 year-old James Powell in 1964; Amadou Diallo in 1999; Patrick Dorismond in 2,000; Mohamed Bah in 2012; and, Eric Garner in 2014.

The New York Kidnapping Club, a precursor of the NYPD -- According to historian Jonathon Daniel Well: "(T)he NY Kidnapping Club was a powerful and far-reaching collection of police officers, political authorities, judges, lawyers, and slave traders who terrorized the city's Black residents throughout the early 19th century. They cared little whether an individual they arrested was in fact an escaped slave or born free. Alongside them stood the city's business community, cheering on every attempt to return fugitives so that peace with the slave South remained intact".

Founded in 1845 as the "Municipal Police" -- NYC's first professional force was modeled on London's Metropolitan Police. This agency was created in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel, Home Secretary of Britain who "developed his ideas while managing the British colonial occupation of Ireland (...) and (who sought) new forms of social control that would allow for continued political and economic domination in the face of growing insurrections, riots, and political uprisings".

The growth of City's Irish population -- As the numbers of Irish residents increased, so did their presence in city-wide positions of power especially in the NYPD. Consequently, Black New Yorkers and other less powerful religious and ethnic groups became the primary targets of the NYPD. "they still beat up Irish people--Irish suspects--but they're also dealing in a more hostile way with newcomers," one historian stated. During riots, she noted, it was common for Irish police to join with Irish mobs against less politically powerful Italians, Jews, and African-Americans".

The Civil War Draft Riot -- In July 1863 a mob, consisting of mainly Irish Catholic New Yorkers, began attacking Black people (blamed by many for the War & the draft) who were lynched from trees & lampposts.

The Lexow Committee -- In 1894 a group of Republican State Senators, called the Lexow Committee, convened to investigate corruption and graft within the NYPD. In what was described as "the most detailed accounting of municipal malfeasance in history", the Committee published a 10,500 page report revealing the unscrupulous inner workings of the department, including "police involvement in extortion, bribery, counterfeiting, voter intimidation, election fraud, brutality, and scams."

The Tenderloin Riot in August 1990 -- The worst in NYC's history since the Draft Riot, this disturbance was triggered by the death of officer Robert Thorpe killed in an altercation with a Black man. According to a contemporary account: "Hundreds of frenzied rioters, including neighborhood policemen, surged through the streets of the Tenderloin, screaming bloody vengeance for Thorpe's murder. They lashed out at any Black people they saw, tearing clothes, breaking limbs, and slashing faces to tatters".

NYPD's Persecution of NYC's Queer Community (1910-1920's) -- In addition to Black people, also on the NYPD's list of so-called "undesirables" in the early decades of the 20th century were queer New Yorkers. In 1923 the New York legislature created the charge of "disorderly conduct -- degeneracy" which was "(t)he first law in the state's history to verge on specifying male homosexual conduct as a criminal offense". The NYPD aggressively enforced the statute; in the first four months of 1925, for example, NYC police arrested 250 people on the charge of "disorderly conduct -- degeneracy".

Harlem Riot of 1935 -- During the disturbance there were 125 arrests, more than 100 injuries, and three deaths. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed a biracial "Mayor's Commission on Conditions in Harlem" to investigate. When the Commission issued its report, identifying "injustices of discrimination in employment, the aggression of the police, the racial segregation" as problems that led to the uprising, La Guardia shelved the document, suppressing it from public view for fear of the "grim picture it painted of conditions among Black New Yorkers."

Harlem Race Riot of 1943 -- A fight between a white police officer and a Black man, Robert Bandy, triggered this disturbance. 6 people died, 550 were arrested, and 185 were injured. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., then pastor of Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church, sought to give insight into Bandy's thinking during the encounter with the officer: he was likely "mad with every white policeman throughout the United States who had constantly beaten, wounded, and often killed colored men and women without provocation".

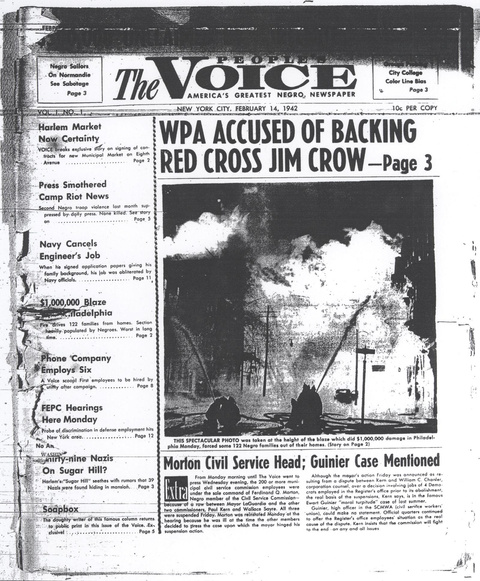

** The People's Voice -- Powell founded this newspaper in 1942. It was based in Harlem with the explicit purpose of serving the African American community. Its reporters carried out independent analyses of incidents of police violence in Harlem, presenting, in effect, an alternative view of what had happened, alternative to the NYPD version which was usually the story that mainstream media published.

1950's NYPD Brutality -- Al Nall, a reporter for the Harlem-based Amsterdam News, noted in 1957 that there was not a week in which the paper was not informed of a police brutality case. He stated: "There were so many police brutality lawsuits and financial settlements that it had become quite expensive for the City". One such case involved the police shooting and killing of veteran John Derrick outside a Harlem bar in 1950. The Congressman from East Harlem at the time, Vito Marcantonio, wrote that the killing of John Derrick was the "height of police violence and brutality against Negro citizens", stating that in "recent years the police have attempted to turn Harlem and East Harlem into a Georgia or Mississippi".

Harlem and Bed-Stuy Riots of 1964 -- In the summer of 1964, an off-duty NYPD officer shot and killed a 15 year old Back student outside his Junior High School "in front of his friends and about a dozen other witnesses". The incident sparked 6 days of violent protests. Wrote Christopher Hayes, an urban historian: "The police marshaled an unnecessarily aggressive response to the protesters, arresting and viciously beating many in the crowd".

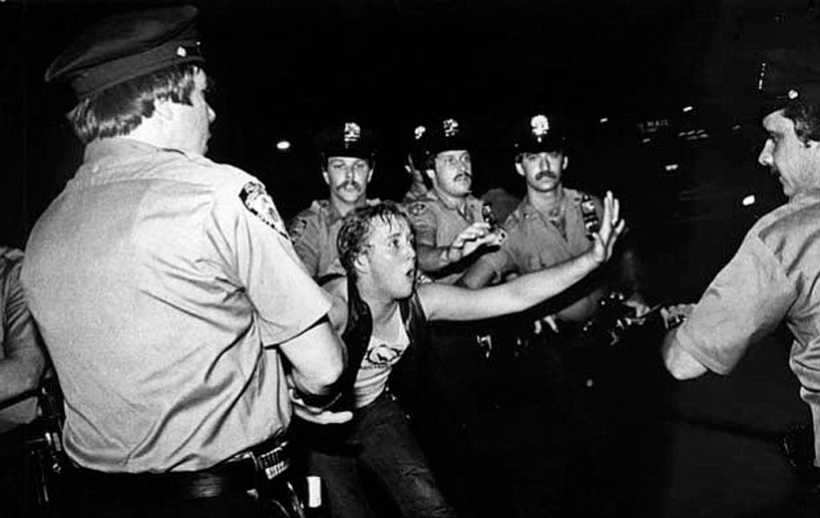

The Stonewall Uprising -- June 28, 1969 -- Located in Greenwich Village, the Stonewall Inn was a popular bar serving a gay clientel. The uprising began when police raided the place in the early hours and began roughly hauling patrons and employees out of the bar. In response to the officers' violent tactics (and decades of mistreatment at the hands of the NYPD), a crowd that had gathered outside of Stonewall began throwing things at the police, igniting a full-scale brawl and what would turn out to be 5 days of protests with 1000's of people participating.

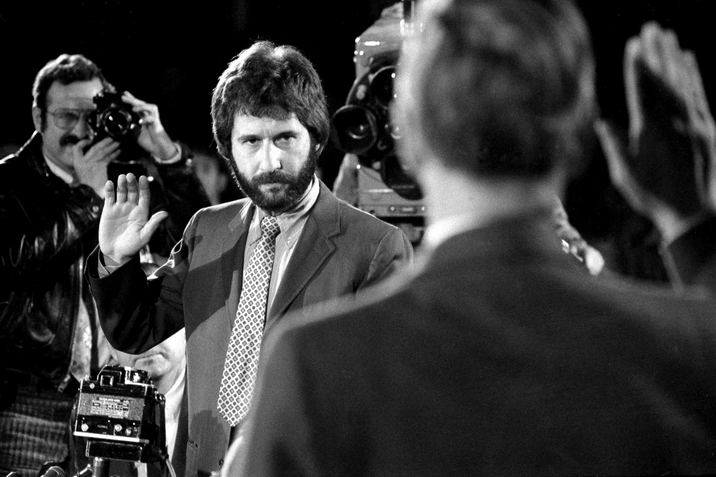

The Dinkins Administration (1990-93) -- The City Hall Police Riot -- The City's first Black Mayor, David Dinkins moved to enhance NYPD oversight. He proposed a bill to change the leadership of the City's Civilian Complaint Review Board to a group consisting entirely of people outside the NYPD. The City's police union vigorously opposed the plan. A rally organized by the union at City Hall, addressed by Rudy Giuliani among others, became violent as 4,000 off duty officers jumped over barricades in an attempt to rush the building. According to the NY Times:

"At 10:50 A.M., a few demonstrators chanting, 'Take the hall! Take the hall!' flooded over the barriers and into the parking lot in front of City Hall, meeting no resistance from the police on guard. Cheering and screaming, thousands of others poured through every side of the park and seethed up the hall steps. Some mounted automobiles and began a raucous demonstration, denting the cars."

Officers referred to Dinkins as a "n***** inside City Hall" and the "n**** mayor", while Mary Pinkett, a Black City Councilwoman, "was trapped on the Brooklyn Bridge and had her car rocked back forth by off-duty officers".

The Giuliani Administration (1994-2001) -- To head the NYPD, Rudy Giuliani appointed Bill Bratton, who was, and remains, a leading law enforcement proponent of broken windows policing, a strategy that targets low level offenses like disorderly conduct and petty larceny as a way to curb serious crimes like rape and manslaughter. While, as Bratton has acknowledged, no studies have ever proven that broken windows is effective in improving public safety, research has documented its undeniably harmful impact on low-income communities of color. The NYPD's own numbers, for example, consistently show over the years that 87-88% of misdemeanor arrests involve New Yorkers of color, supporting, in effect, the criticism that broken windows tactics target Black and Brown communities for petty offenses that have been virtually decriminalized in White areas.

What broken windows did provide the Giuliani Administration, however, was the means to use the NYPD to address the City's homeless problem, at least in its short term visibility. According to the NY Times: "The police began rounding up the homeless in a series of Manhattan sweeps in the mid-1990's, and many either moved out of tourist areas and went to less patrolled places -- or faced arrest and court summonses for such public nuisance violations as impeding the flow of pedestrian traffic. Police said . . . that the homeless could be arrested on charges of disorderly conduct or trespassing."

The Bloomberg Administration (2002-2013) -- Michael Bloomberg took office less than 4 months after the terrorists attacks on lower Manhattan. His NYPD spent the following years executing a clandestine spying program monitoring daily life in the City's Muslim communities. The practices of the Demographics Unit created "a pervasive climate of fear" among NY's Muslims that "encroached upon every aspect of individual and community life". The NYPD refused to acknowledge the existence of the unit until it was exposed in a series of Pulitzer Prize winning articles published in 2011 by the Associated Press. A year later, the chief of the NYPD Intelligence Division admitted in sworn testimony that over its 6 year tenure "the unit tasked with monitoring Muslim-American Life had not yielded a single criminal lead".

Stop and Frisk -- During the Bloomberg years, the NYPD use of stop and frisk skyrocketed, going from 97,296 stops in 2002 to 685,724 stops in 2011, a 600% increase. Under Bloomberg and his police chief Ray Kelly, "stop and frisk" gave NYPD officers free rein to detain, question, and frisk civilians without probable cause. The NYPD's own numbers exposed the extent of the tactic's deep racist impact: though Black and Latino males between the ages of 14-24 accounted for only 4.7% of the City's population in 2011, they were victims in 41.6% of the stops. The number of stops of young Black men, ages 14-24, exceeded the entire City population of young black men, 168,126 as compared to 158,406.

The de Blasio Administration (2014-2021) -- Bill de Blasio had campaigned as a reformer, but his first official appointment being Bill Bratton as the NYPD's new chief gave advocates for changes in policing cause for concern. The Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP), a non-profit group dedicated to exposing and ending abusive and biased NYPD practices, devised an independent means for evaluating police arrest practices. Everybody who gets arrested in NYC has to be arraigned, so in the summer of 2014, PROP began sending its representatives into the arraignment parts of the City's 4 mayor boroughs: Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens.

During the course of de Blasio's mayoralty, PROP issued 12 court monitoring reports, the first in July 2014 which found that of the 747 arraignment cases observed, 667, 89.3%, involved NYers of color. In April 2022 PROP issued the final de Blasio era report that found that of the 6,722 cases observed from June 2014 through December 2021, 6004, or 89.3%, involved NYers of color. The consistency of PROP's findings are striking, as is, sadly, the continuing racism of NYPD arrest practices.

The George Floyd Protests -- On May 25, 2020, in actions caught on video, Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd, a Black man charged with passing a counterfeit $20 bill. Protests and marches took place in every corner of the US. In NYC, NYPD officers overreacted with eyewitnesses and videos documenting numerous cases of officers using excessive force. The NY Times released 64 videos accompanied by narrative reporting. "A review of the videos, shot by protesters and journalists", The Times stated, "suggests that many of the police attacks, often led by high-ranking officers, were not warranted".

Still, de Blasio defended the NYPD's actions while accusing the protesters of provoking the police. His apologia prompted 400 members of his own staff to write an open letter condemning his response and demanding increased police accountability.

The Adams Administration (2022-2023) -- A former NYPD transit officer and police captain, Eric Adams made clear his pro-police views during his 2021 campaign for mayor and continues to make them clear in his first year in office. He has, for example, taken these steps: appointed as NYPD Commissioner Keechant Sewell who immediately announced her support for broken windows tactics; and, revived a controversial plainclothes unit disbanded by the de Blasio administration in 2020 after its harsh practices were declared unconstitutional.

NYPD Arrest Practices in 2022 -- Racist and On the Rise: NYPD arrest practices have become more aggressive under Adams. According to data produced by the NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS), the number of NYPD felony and misdemeanor arrests in 2022 --156,836 -- increased by 20% over 2021 arrest numbers --131,731. DCJS data also documented the continuing racism of NYPD arrest practices for 2022. 88% of misdemeanor arrests, which make up the majority of NYPD arrests, involved NYers of color. Over 52% of felony arrests involved Black NYers who make up 25.1% of the City's population.

"Its story has assumed an increased

relevance during an era when the issue of abusive and biased policing has been the focus of heightened public concern."

INTRODUCTION

We at the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP) believe that the history of the New York Police Department is very much worth telling. Its story has assumed an increased relevance during an era when the issue of abusive and biased policing has been the focus of heightened public concern. It has also been a time, perhaps contradictorily, that many jurisdictions in the US, including New York City, have not only maintained their police departments, but expanded them.

As our title suggests, this report focuses on the notorious policies, practices, and actions that have characterized far too much of the NYPD’s history. AWe hope this document dramatically increases awareness of the extensive harm that the NYPD has inflicted on the city’s people, especially by its victimization of Black New Yorkers and other New Yorkers of color, throughout its long history from the 19th century to the present day.

As the title here also conveys, the entire body of the report — all the accounts, all the stories it presents — are true. Some content may challenge credibility, may shock the conscience. But know that this history’s authors have done their homework and their research and that reliable sources for all of it have been or can be provided. PROP views preparing and publishing this document as a very serious undertaking, one that could possibly be part of a movement to make our great city even greater, to make it a place that provides a safe, just, and inclusive life experience for all New Yorkers.

THE BEGINNINGS

Groups empowered mainly by business owners and the wealthy to maintain order and restrict public vice have operated in the region currently constituting New York City since the early 1600s. These efforts began with legal officers and the ‘Rattlewatch’ under Dutch rule, which then extended to the introduction of the City’s first uniformed policemen, and later, the constable’s watch under British rule through the late 1700s.

Harper's Weekly: "Charge of the Police on the Rioters at the Tribune Office," Harper's Weekly, August 1, 1863.

It wasn’t until the US gained independence from the British following the Revolutionary War that New Yorkers established a modern police force in their own right. Founded in 1845 as the “Municipal Police”, NYC’s first paid professional force, consisting of 900 officers, was modeled on London’s Metropolitan Police. This agency was created in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel, Home Secretary of Britain, who “developed his ideas while managing the British colonial occupation of Ireland (…) and (who sought) new forms of social control that would allow for continued political and economic domination in the face of growing insurrections, riots, and political uprisings.”

Interestingly, charges about the force’s use of violence date back to the first years of its founding, when in 1846, during its full first year of operation, “twenty-nine people filed complaints with the city clerk charging that they had been assaulted by police officers.”

THE “KIDNAPPING CLUB” AND THE TREATMENT OF BLACK RESIDENTS (1830'S-1860'S)

Given the practices of its immediate forerunners, it is perhaps not surprising hat the city’s new police force applied its harshest practices to two groups of NYC’s most marginalized citizens, recent Irish immigrants fleeing the terrible impact of the potato famine on their homeland, and freed Black people, free because New York State had officially abolished slavery in 1827. The Municipal Police’s less formal precursors often seemed more concerned with protecting local business interests than with the well-being of the City’s most vulnerable residents. This skewed set of priorities was perhaps most clearly exemplified by the New York Kidnapping Club. According to historian Jonathan Daniel Wells:

“[T]he New York Kidnapping Club was a powerful and far-reaching collection of police officers, political authorities, judges, lawyers, and slave traders who terrorized the city’s Black residents throughout the early nineteenth century. They cared little whether an individual they arrested was in fact an escaped slave or born free. Alongside them stood the city’s business community, cheering on every attempt to return fugitives so that peace with the slave South remained intact.

New York City’s economic growth depended to a significant degree on the existence of human slavery in the American South. Wall Street played a large role in financing the South’s cotton industry – responsible, for instance, for exporting crops to textile mills in the northeast and Britain through New York City-based businesses, brokers, and financiers.⁶ Police forces in New York and other northern American cities were actively involved in safeguarding those interests.

Perhaps no individual promoted this dubious arrangement more assiduously than Captain Isiah Rynders of the U.S. Marshals, who fled to New York City after reportedly killing a man on a Mississippi River steamboat over a card game. Upon his arrival, he made Black New Yorkers his target, using the Constitution's Fugitive Slave Clause to promote the patrol and capture of Black New Yorkers to be “returned” to their southern enslavers.

Making matters worse: judges’ decisions often ensured that it made little difference whether a Black person in New York was born free or had in fact escaped bondage. Magistrate Richard Rikers–the judge after whom the infamous Rikers Island Jail Complex is named–was all too often willing to send “the accused to southern plantations with little concern and often even less evidence.” Rikers “used his wealth and power as a presiding judge over New York City’s primary criminal court to see to it that African- Americans were swiftly deemed ‘fugitive’ runaway slaves, without granting them due process to prove that they were actually free.”

RISE OF THE IRISH IN THE NYPD (LATE 1850’S —1860’S)

As New York’s Irish population grew, so did their presence in city-wide positions of authority, particularly within the NYPD. They had been dismissed and dehumanized by Anglo-protestant America which deemed them a barbaric people. Newspapers and cartoons depicted the Irish as a degenerate race. “Frequently apelike, always poor, ugly, drunken, violent, Paddy and his ugly, dirty, fecund, long-suffering Bridget differed fundamentally from the visual depictions of sober, civilized Anglo-Saxons.” In the words of Frederick Douglass, “The Irish needed only black skin and wooly hair to complete their likeness to the plantation negro.”

But the greater their numbers grew, the harder it was to ignore the presence of the Irish as voters and contributors to the labor force. New York City’s Irish population began to catch on to the city’s shifting racial and power dynamics, and many realized how the newfound authority that came with the job of policing would allow them to distance themselves from other persecuted populations that were moving into the city, particularly Black Americans and Caribbean immigrants. Non-Anglo-Protestant whites who had once been vilified by the business community were occupying more positions of power, and as such, they could no longer be scapegoated for the City’s flaws as they had been decades prior.

Consequently, Black New Yorkers and other less-powerful religious and ethnic minorities soon became the primary targets of the police: “[t]hey still beat up Irish people—Irish suspects—but they’re also dealing in a more hostile way with newcomers,” historian Johnson says.¹² During riots, she notes, “it was common for Irish police to join forces with Irish mobs against less politically powerful Italians, Jews or African-Americans.”¹³

With all the newcomers, Manhattan quickly began to run out of living space: Irish, Italians, Jews, Cubans, and Blacks were competing for territories, and animosities quickly formed on the basis of race. Finding safety and community amongst their own people, many newly-arrived Black people from southern states and the Caribbean ended up settling in the Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem.

POLICING DURING THE CIVIL WAR: DRAFT RIOTS AND RACIAL RESENTMENT IN AN ERA OF ECONOMIC DOWNTURN (1860S-1880S)

In the 1860s the United States plunged into Civil War. New York City’s working people bore the brunt of the resulting economic and political strain which included the city’s changing demographic and power dynamics. Between 1850 and 1860 the population of Manhattan had risen by almost 100,000, setting the stage for competition among the populace for jobs, homes, territory, and political influence.¹⁴ These tensions literally and figuratively exploded when the City passed a series of Draft Laws to shore up union support for the war. The laws dictated that “all single men [...] between the ages of twenty and forty-five and all married men between twenty and thirty-five” could be compelled to serve in the Union Army. But a provision carving out an exception for those wealthy enough to buy their way out of harm’s way by hiring a substitute or paying $300 to the government would tip the scales from anger to violence.

On July 13, 1863, with the second drawing of the draft, the city descended into mayhem: rioters, most of whom were Irish-Catholic, targeted wealthy individuals by their clothing and ransacked their homes.

Before long the mob began attacking Black people, who the Irish blamed, in part, for the war and the draft. They lynched people from trees and lampposts, and even attacked the Colored Orphan Asylum, a “symbol of white charity to blacks and of black upward mobility.” Mayor George Opdyke asked the Secretary of War for troops to tranquilize the city’s “infected” districts. President Abraham Lincoln had to redirect five regiments of the Union Army to New York City from Gettysburg. “Faced with tenement snipers and brick hurlers, soldiers broke down doors, bayoneted all who interfered, and drove occupants to the roofs, from which many jumped to certain death below.”¹⁹ It wasn’t until the following Friday, after the chaos had prevailed for five days, that order was restored to the city.

Many New Yorkers, including the wealthy class, were thoroughly shaken by the riot. The Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor stated that the riots were a sign of a “dangerous class” of citizens, and that it was in the hands of the gentry to carry out the “moral and physical elevation of these ignorant, semi-brutalized masses.”

In the years both preceding and following the Draft Riot, young, white male immigrants did not have access to the same jobs as Anglo-protestant New Yorkers, and many resorted to illicit money-making schemes and violence through local gangs. The Italian “Five Pointers”, the Jewish “Eastmans”, the Irish “Hudson Dusters” and “Gophers”—such groups began to emerge in the second half of the 19th century, and were united over their common residences and ethnicities.

Fear-wrought communities and business leaders turned to police to resolve the violence. Officers were encouraged by their superiors to ‘beat senseless’ any suspected gang members in their patrol areas. “As strong- arm tactics won praise from local business interests, the department made nightsticks mandatory equipment for all officers, and patrolmen increasingly wielded their clubs as a means of preserving order and establishing authority.”

NYPD CORRUPTION AND THE LEXOW COMMITTEE (1890’S)

In 1894 a group of New York Republican state senators, called the Lexow Committee, convened to investigate corruption and graft within the police force. In what was described as “[t]he most detailed accounting of municipal malfeasance in history.”²³ The Committee published a 10,500 page report that revealed the unscrupulous inner-workings of the department, including “police involvement in extortion, bribery, counterfeiting, voter intimidation, election fraud, brutality, and scams.”

Whereas the department had been allotted $5.1 million in funding from the city for its annual budget, the force amassed a total of $15 million by unlawful means–including $8.1 million from brothel contributions alone. One brothel owner testified that when she tried to close her business, the police demanded it remain open so that they could continue to collect monthly fees. The report also found that individual officers were well- versed in figuring out ways to promote their own careers. Many cops who engaged in electoral ballot fraud were often first in line when it came time for department leadership to dole out promotions.

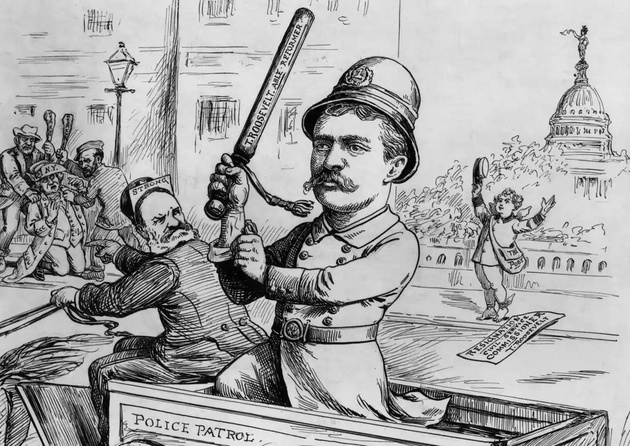

The public was outraged by the Lexow Committee’s findings, and in 1895 elected reformist William Lafayette Strong as the 90th Mayor of New York City. That same year, Strong appointed Theodore Roosevelt to head the Board of Police Commissioners. Roosevelt would be credited with standardizing many department practices and strengthening the qualifications needed to become an officer–emphasizing the importance of physical and mental ability over political influence. But his push to drive out public vice–such as his attempted ban on Sunday drinking in saloons– served to dampen his once-glowing reputation.

In 1898, the City of Brooklyn, Queens County, and Richmond County (present day Staten Island) joined the Bronx in being officially absorbed into the City of Greater New York, paving the way for today’s modern-day NYPD. Inscribed within the 1,250 pages of the Greater New York Charter was the establishment of the “New York Police Department”, which now included eighteen new precincts from various parts of Queens, Kings, Richmond, the Bronx, and New York counties, and would be tasked with presiding over three million or so city residents.

POLICING AT THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY

In 1901, “to curb confusion and dissent” within the NYPD’s administration, the New York State Legislature passed a bill that assigned a single commissioner to oversee the entire newly minted department.³³ Mayor Robert Van Wyck appointed Michael Murphy to serve as the modern NYPD’s first leader.

Around this same time, millions of immigrants began flocking to America, especially to urban areas like New York City in search of work or to escape the economic hardship and/or political oppression that plagued their home countries. But while New York’s Black population tripled from below 30,000 residents to over 90,000 between 1880 and 1910. Black migration to New York City was “dwarfed by the immigration of Europeans” during the same period.³⁵ A result of these trends took the form of overt racism by the white populace who dominated the workforce and controlled the majority of the city’s wealth. Black newcomers were often relegated to the bottom rung of the social and economic ladder. White residents, no matter their socioeconomic status, were mostly unified in their antagonism toward their new neighbors.

Many Black newcomers in the early 20th century moved into the Tenderloin District, a red-light zone that originally ran in the area now surrounding modern-day Herald Square, but that had begun expanding northward to 57th Street and west to Eighth Avenue by the turn of the 20th Century, absorbing parts of what is now known as NoMAD, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, the Garment and Theater Districts. As Black residences continued to expand east toward 9th Avenue, tensions escalated between Black and Irish gangs, who fought violently over territory.³⁶

These heightened strains eventually devolved into the Tenderloin Race Riot of August 1900, the worst in New York City’s history since the Draft Riot of 1863.³⁷ According to a report written by the Citizens Protective League, a group created in response to the city’s unwillingness to punish police brutality, a Black woman by the name of May Enoch was waiting on a street corner for her partner, Arthur Harris, when she was grabbed by undercover police officer Robert Thorpe who accused her of soliciting sex.³⁸ When Harris exited a nearby saloon and confronted Thorpe, the officer hit Harris in the face with his billy club, prompting Harris to defend himself by grabbing his pen knife and stabbing the undercover officer three times in the abdomen before fleeing.³⁹ Thorpe was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital where he succumbed to his wounds the next day. During his funeral, rumors quickly spread of police officers’ intentions to “punish the Negroes.”

Later that night and in the following days from August 15th through August 17th, the Tenderloin neighborhood erupted into chaos:

“Hundreds of frenzied rioters, including neighborhood policemen, surged through the streets of the Tenderloin, screaming bloody vengeance for Thorpe’s murder. They lashed out at any black people they saw, tearing clothes, breaking limbs and slashing faces to tatters. Innocent bystanders, men and women alike, were attacked and pelted with clubs and brickbats. Every 8th Avenue streetcar was halted and boarded, the hoard dragging their targets out into the streets and mauling them.”

As crowds of Irish residents spilled out onto Eighth Avenue screaming “Lynch the n*****s!” They were joined by members of the predominantly-Irish police who had been “seized with a desire of vengeance on Negroes generally,” clubbing black New Yorkers with their nightsticks and shooting their revolvers at apartment windows. Newspapers covering the scene reported that the police could have broken up the mobs “immediately and with little difficulty.” An appeal to the Mayor published by the Citizens Protective League accused policemen of making “no effort” to protect those individuals bearing the brunt of the attack:

“[Policemen] ran with the crowds in pursuit of their prey; they took defenseless men who ran to them for protection and threw them to the rioters, and in many cases they beat and clubbed men and women more brutally than the mob did. They were unrestrained by their superior officers. It was the night sticks of the police that sent a stream of bleeding colored men to the hospital, and that made the station house on West 37th Street look like a field hospital in the midst of battle. Men who were taken to the station house by officers and men in the station house were beaten by policemen without mercy, and their cries of distress made sleep impossible for those who lived in the rear of the station house.”

A grand jury refused to indict any officers involved and an internal NYPD review fully exonerated all accused policemen for any crimes committed — instead, the review commended officers for their “prompt and vigorous action.” In response, the City’s leading Black ministers formed the Citizens’ Protective League to implore the Mayor to further investigate the countless attacks against Black residents.⁴⁷ In response to their request, Mayor Van Wyck announced that all “investigations” would be handled by the Board of Police–resulting in a report that summarily glossed over witness testimonies and overlooked discrepancies in police accounts of what happened.

he report ultimately concluded that no police were at fault regarding the injuries sustained by residents during the riot. Indeed, the NYPD’s position was succinctly summarized in the words of the Commissioner at the time, Bernard York: “The real offenders,” he concluded, “were the negroes who insisted in getting into the disorderly crowds that were pursuing them.”

The Tenderloin Riot and subsequent San Juan Hill Riot of 1905, which mirrored its predecessor almost exactly, exposed the NYPD’s violent practices and the harm they inflicted on the City’s nascent Black communities. Also true was that the NYPD’s use of unnecessary force against Black New Yorkers was not limited to instances of protest or conflict on the street. In fact, mirroring Officer Thorpe’s treatment of May Enoch just for standing on a street, common instances of NYPD mistreatment of Black community members occurred when they were simply outside and occupying public spaces.

NYPD’S PERSECUTION OF NEW YORK CITY’S QUEER COMMUNITY (1910'S-1920'S)

Also on the list of the NYPD’s so-called “undesirables” in the early 20th Century were queer New Yorkers. Queer people in the 1910s convened in saloons throughout the Brooklyn Navy Yard–an area well known for gay cruising. It was one of the few centers within the City that allowed gay people to express themselves without fear of persecution. One bar in particular–tended by barkeep Antonio Bellavicini and located at 32 Sands Street--was flagged by police after a previous owner had been caught gambling.⁴⁹ One NYPD officer, Patrick Clark, described the establishment as “frequented by degenerates…men, they were powdered and painted up and their voices feminine.”

On the night of January 14, 1916, the police disguised Officer Harry Saunders as a navy soldier and sent him into the bar to identify and arrest individuals soliciting sex. Within twenty minutes of Saunders entering the bar, the police had arrested seven individuals, including bartender Bellavicini. Authorities accused him of running a “disorderly house,” defined by the penal code as “a house of ill-fame and assignation, and a place for the encouragement and practice by persons of lewdness, fornication and unlawful sexual intercourse, and other indecent and disorderly acts and obscene purposes therein [...]”

At this point in New York State’s legal history, there weren’t laws that prohibited identity, only those that prohibited specific behaviors. While queerness itself wasn’t criminalized, gay men wearing makeup or women’s clothing were. Looking to justify their arrests during the raid of 32 Sands Street, officers embellished their testimonies, claiming that the men in the bar hadn’t just solicited sex, but were also wearing makeup and had powder puffs in their hands; only with these testimonies could the men be “held accountable” and charged with vagrancy or sex work, because the state didn’t yet have the legal framework to charge people based on their gender or sexual identity.

This state of affairs changed, however, in 1923 when the New York legislature created the charge of “disorderly conduct – degeneracy.”⁵⁴ In George Chauncy’s Gay New York, he explains that this legislation was “[t]he first law in the state’s history to verge on specifying male homosexual conduct as a criminal offense.” The regulations associated with the new law “explicitly prohibited gay men and women from gathering in licensed public establishments [...] They threatened to destroy the business of any bar or restaurant proprietor who served a single drink to a single gay man or lesbian, to close any theater presenting a play with gay characters, and to prevent the distribution of any film addressing gay issues.”

In the first four months of 1925, NYC police arrested 250 people on the charge of “Disorderly Conduct—Degeneracy.”⁵⁷ Upon learning of these arrests, the General Secretary of the Committee of Fourteen, an influential anti-vice group, Frederick Whitten, wrote to the NYPD’s Deputy Chief Inspector Samuel Bolton: “[t]here is a feeling [...] that the person guilty of such acts – and they were not limited to the uneducated or lower classes – are mentally deranged [...] if you think as I do, that this problem is one which should, in view of the large number of cases now before us, have your particular attention, will you not make an appointment with me that we may discuss it? I think I can suggest a solution for former difficulties.”

PROHIBITION (1920'S-1930'S)

During this period the NYPD faced a substantial challenge in trying to enforce the new constitutional ban prohibiting the sale of alcohol. The Volstead Act of 1919, which outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, combined with the widespread joblessness brought on by the Post-WWI recession, led to a real rise in crime in New York City. NYPD patrolmen began phasing out indiscriminate street clubbings and replacing them with violent “third degree” crime control tactics, which included “prolonged grilling, food and sleep deprivation, and psychological coercion” that were carried out within the confines of police stations to avoid public scrutiny.⁶⁰ These tactics of torture played a significant role in undermining the image of a benevolent, crime-fighting police force during the Prohibition Era when arrests, prosecutions, and civilian complaints of police brutality climbed sharply and served to seriously tarnish the department’s reputation.

In New York State, prohibition enforcement was largely shaped by the Mullan-Gage Act passed in 1921. This law included many intrusive provisions; for example, it empowered law enforcement officers to search for alcoholic beverages whenever and wherever they wished. Under Mullen- Gage, the strictest “dry law” in NYS history, police did not need either probable cause or a search warrant, giving the aura of a Gestapo-like police force.

Within two weeks of the law’s passage, “prohibition cases on local court dockets increased tenfold, and local prosecutors complained that they could not find enough jurors to hear the flood of new cases.”⁶¹ Over the next two years, the Manhattan grand jury would hear more than 6,900 prohibition cases–with one enforcement unit, dubbed “Whalen’s Wackers” after Commissioner Grover A. Whalen, allegedly raiding sixty speakeasies per night in 1928 alone.

In 1922 the City Magistrate Joseph Corrigan said that he had “never seen conditions so bad among policemen as in the past few months…Raid after raid is being brought into these courts despite the fact that magistrates have been declaring them illegal. The police are running roughshod over the rights of the people.”

At the same time prohibition cases began to rise, corruption within the police department became a pervasive issue. Speakeasy owners and operators often paid officers to ignore liquor violations and notify them of imminent raids. Some officers took on a more direct role in organized crime itself, directing customers to speakeasies, bootlegging, and peddling confiscated liquor.

Adding to the problem, individuals who refused to serve alcohol to officers, pay bribes, or incorporate them in their illicit schemes often faced harsh consequences. Such was the case in 1924 when an off-duty officer shot two nightclub managers after they contested a $200 bribe, and again in 1927 when a Brooklyn cabaret owner was shot by two uniformed officers after refusing to serve them drinks.

Mirroring the plight of many New Yorkers looking to make ends meet, in 1930 a widow began selling alcohol for extra cash — two undercover officers assaulted and arrested her after she refused to pay a $500 bribe. In each of these instances, “[r]estaurant operators were thus placed in an awkward position: If they served liquor to police officers, they risked shakedowns or prosecution under prohibition laws; if they refused, they might incur the wrath of police who viewed after-hours tippling as a professional perk.”

STOCK MARKET CRASH AND THE HARLEM RIOT OF 1935

After the stock market crashed in October 1929, NYC saw increasingly difficult economic times. Within the span of months, countless NYers had lost their jobs, homes, and livelihoods. By the winter of 1932-33, 2,000 NYers were sleeping on the streets, and by 1933, one-third of the city’s workforce was unemployed.⁶⁸ New York was “the symbolic capital of the Depression, the financial capital where it had started, and the place where its effects were most keenly felt (…)”

Hard times coupled with ongoing racial tensions created conditions for conflict to flourish. These trends eventually boiled over, providing the trigger for the Harlem Riot of 1935. On March 19th Lino Rivera, a 16-year old Black Puerto Rican boy, was caught stealing a penknife from the S.H. Kress dime store located at 256 West 125th Street.⁷⁰ After an employee at the store threatened to take Rivera into the store’s basement and “beat the hell out of him”, Rivera bit the employee’s hand.⁷¹ The store manager called the police before letting the boy go. As a crowd began to gather outside the store, a woman who had witnessed the boy’s initial apprehension shouted that Rivera was being beaten–a rumor that the crowd took as fact when an ambulance later arrived to treat the employee who had been bitten.

More than 10,000 people gathered in the streets to protest against the perceived brutality. After someone threw a rock through the window of the S. H. Kress store, the demonstration devolved into widespread looting. Rioters targeted white-owned businesses as police arrived to try to disperse the crowd. Some shopkeepers sought to protect their property by posting signs such as “Black owned” and “We employ Black people” in their windows.⁷² Looting continued throughout the night and into the following morning, resulting in property damage to about 200 stores. There were also 125 arrests, more than 100 injuries, and three deaths.

Under pressure to uncover the riot’s cause, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed a biracial “Mayor’s Commission on Conditions in Harlem” to investigate the disturbance.⁷⁴ When the Commission issued its report later that year, identifying "injustices of discrimination in employment, the aggressions of the police, and the racial segregation" as conditions which led to the uprising, La Guardia shelved the committee’s report.⁷⁵ The mayor kept it from the public for fear of exposing the extent of police misconduct and the “grim picture it painted of conditions among Black New Yorkers.”

1943 HARLEM RACE RIOT

The early 1940s saw the start of the Second Great Migration. Large numbers of southern Black Americans (and some Caribbean immigrants) relocated to major cities across the U.S. to escape racial prejudices and to take advantage of the ballooning labor demand that resulted from much of the country’s male workforce being drafted to fight overseas. New York City’s Black population grew from 458,000 to 547,000 between 1940 and 1945--with many settling in pre-established Black communities in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant where they could more easily avoid discriminatory housing policies.⁷⁷ Unfortunately, living conditions often proved difficult for the newcomers.

Many were crammed into “dark, unpleasant houses with steep stairs and narrow halls, where the rooms [were] too small, the ceilings too low, and the rents too high”. It was a common sight to see apartments with “a dozen names over each bell [...] full of lodgers in every alcove, [with] everything but the kitchen rented out for sleeping.” Black New Yorkers faced constant racial discrimination—in housing, in jobs, and at the hands of the police. Circumstances were ripe for a public disturbance.

The NYPR Archive Collections, August 2, 1943

In 1943, a white police officer in the Braddock Hotel arrested a Black woman for disorderly conduct after she had allegedly gotten into a fight with an elevator operator. When bystander Florine Roberts intervened and demanded the woman be released, her son, Robert Bandy, in an attempt to defend his mother, got into an altercation with the cop. Bandy seized the cop’s nightstick, and the cop retaliated by shooting him. Neither of the men’s injuries proved fatal, but the community had caught on to the situation, and rumor soon spread that “a white cop killed a Black soldier.”

Crowds gathered outside the Braddock Hotel and the hospital where the two men were being treated. Once the officer was brought back to the Twenty-Eighth Precinct house, over three thousand people swarmed the police station. They threw bricks and detritus, overturned cars, and fought with police and the police in turn bludgeoned, brutalized, and rounded up scores of people. By the time the crowd had been dispersed, 6 people had died, 185 people were injured, and 550 were arrested.

After the riot Adam Clayton Powell Jr., then pastor of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, gave insight into Bandy’s train of thought when he went for the officer’s nightstick: he (Bandy) was likely “mad with every white policeman throughout the United States who had constantly beaten, wounded, and often killed colored men and women without provocation.”

THE PEOPLE’S VOICE

In 1942 Powell founded The People's Voice, a newspaper based in Harlem, with the explicit purpose of serving the African American community. As part of its news coverage, the paper conducted its own explorations into local racial issues, especially regarding New York City's police force. For example, in April 1943, police closed a dance hall called the Savoy Ballroom due to alleged reports of prostitution in the location. However, Black leaders speculated it was due to racial integration on the dance floor and, in response, The People's Voice launched an investigation of local White dancing clubs. Additionally, in the spring of 1942, a Black Harlem resident, Wallace Armstrong, was killed by a White policeman, so The People's Voice focused an investigation into the police department while Powell organized protests.

In fact, a major aspect of the paper's reporting involved publishing articles on allegations of police misconduct. Adams hired several professional journalists–one of their assignments was to carry out an independent analysis of what happened regarding incidents of police violence in Harlem. The reporters' job was to interview the victims of purported NYPD violence, if they were still alive, and their family members and also neighborhood residents who witnessed the incidents. The clear purpose of this approach was to present an alternative view of what had happened, alternative to the version produced by the NYPD itself which was usually the story that mainstream media published.

These practices of The People's Voice earned the censure of Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine, who condemned Powell and his paper's activities as “dangerous” and “rabble-rousing.”

POLICE BRUTALITY IN THE 1950S

Al Nall, a writer for the Harlem-based Amsterdam News, noted in 1957 that there was not a week in which the paper was not informed of a police brutality case. He reported that “There were so many police brutality lawsuits and financial settlements that it had become quite expensive for the city.”

One such instance occurred on December 7, 1950, when veterans John Derrick, Zach Milline, and Oscar Farley were stopped, questioned, and shot at without notice by two white patrolmen. The three friends were leaving a bar in Harlem after celebrating Derrick’s medical discharge from the army. Derrick, who had suffered injuries from the Korean War, was shot in the heart and died soon after.

As the investigation into Derrick’s death continued, telling details arose. Eyewitness Geneva Swagerty, who saw the shooting from her home on 119th Street, testified that the police that shot Derrick did so while his hands were already raised and no weapon was to be seen.

Derrick reportedly had over $3,000 of his savings in his pocket at the time of the attack, which vanished mysteriously after he was killed. The officers attempted to justify their use of force by claiming that the men had a gun, though eyewitnesses indicated otherwise. In her sworn affidavit, Swagerty testified that the police shot Derrick while his hands were raised and that she saw no gun on his person; Derrick’s companions also said under oath that the police found no weapon upon immediate search.

On December 10, three days after the shooting, with reasonable evidence to suggest the pistol had been planted on Derrick, the NAACP called on city officials to investigate the shooting and suspend the two accused officers. Nevertheless, the District Attorney declared that the officers were “properly performing their duties,” and in 1951 the grand jury ruled that “it had found no basis for an indictment.”

U.S. Representative Vito Marcantonio, who served East Harlem in the House of Representatives, wrote in The Daily Worker that the killing of John Derrick was the “height of police violence and brutality against Negro citizens,” arguing that in “recent years the police have attempted to turn Harlem and East Harlem into a Georgia or Mississippi.”

The John Derrick case was not the only instance of police brutality against Black New Yorkers during this era that The Amsterdam News reported. The paper, for instance, reported in May 1955 that an officer from the 28th precinct beat Elbert Dukes, a nine-year old child, across the face. Dukes stated that the cop took him into custody while he was waiting for a train and attacked him at the precinct.

Two weeks later, The Amsterdam News reported that a grand jury had exonerated detective John McEnry in the death of forty-seven-year-old Edward Johnson–a man who had been standing at 106th Street and Central Park West and was, according to the detective, ‘looking suspicious.’ McEnry claimed that Johnson had started kicking him during the confrontation, resulting in him taking a fall and suffering a skull fracture and hemorrhage. But Johnson’s family attorney, Henry Williams of the NAACP Legal Redress Committee, argued that it was impossible that Johnson could have kicked the detective because Johnson had suffered from severe arthritis in both legs since 1943.

Also, in April 1955 patrolman Herbert Fisher and city marshal Morris Heyman were accused of “clubbing, shoving, flooring, kicking and beating” Cleo McCaskill, a pregnant mother of five. McCaskill, who was being evicted from her apartment, had objected to the marshal placing her furniture in the street. She was arrested “at gunpoint” and charged with assault.”

HARLEM AND BED-STUY RIOTS OF 1964

In the summer of 1964, an off-duty officer shot and killed 15-year old Black student James Powell in front of his friends and about a dozen other witnesses outside his junior high school on East 76th street in Manhattan.⁹⁹ The incident sparked six days of violent protests that jolted the city. “The police marshaled an unnecessarily aggressive response to the protestors, arresting and viciously beating many in the crowd,” said Christopher Hayes, an urban historian at the School of Management and Labor Relations. “When it was over, the police had arrested hundreds, injured thousands, and killed at least one man. Hundreds of businesses were looted or damaged.”

While the media took different positions on the riot, it initially avoided placing responsibility for the disturbance at the NYPD’s doorstep: Time magazine targeted the ”hate-preaching demagogues” who “took to the street corners” and “raunchy radicals” who ‘issued inflammatory broadsides.” The New York Times chronicled the “groups of Negroes [that] roamed the streets, attacking newsmen and others” and were also on rooftops hurling bottles and bricks at police on the street, who responded by firing warning shots “over the attackers’ heads.”

As the dust settled and more than one hundred victims were treated at Harlem and Sydenham hospitals, eyewitness accounts of police brutality garnered some public attention. Doris Berry, an African American woman from Central Harlem, told The New York Times that she was out on the street looking for her mother who had been lost in the mob when a white policeman aimed his gun at her and shot her in the right knee. “I thought he was just shooting blanks until I got hit in the leg,” she recounted, “[and] the cops just left me there. I had to find a taxi to get to the hospital.”

Thessolonia Cutler, another Harlem-based African American woman, reported to The New York Times that she witnessed police “beating up everyone [to the point that] there was nothing but smoke and gunshots for blocks around” while heading home from work. She was later shot in the back of the head while standing in her doorway.¹⁰⁶

Simone Montgomery, also a Harlem-based African American woman, wrote to Mayor Robert Wagner and Police Commissioner Michael J. Murphy detailing her experience:

“She had heard shots and as she looked out her window saw fifteen or more cops ‘running up and down the block firing shots in the air and chasing people.’ Two of them looked at her and shouted, ‘Get the fuck out of the window.’ Then, she wrote, they ‘fired directly at me.’ One bullet just missed her head, traveled through her drapes, grazed a wall, and ricocheted off the ceiling to the floor of her apartment. The second bullet smashed through a windowpane and into the ceiling [...] ‘There is no doubt that the officers fired directly at me, as can be evidenced by where the bullet struck in relation to where I was standing.’ She also claimed that the words she heard one officer say to the other was further proof that she was a target: ‘We might have got the black bastard’”

Harlem’s representative in the U.S. House, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., remarked that what had happened in his district was “without precedent in the history of any police department in any city, including the Deep South. New York City ought to hang its head in shame.”¹⁰⁸ In fact, the NYPD’s use of force was sufficiently extensive that “by the third day of the riot, the police had fired so many rounds that they had exhausted their ammunition supply.”

RAIDS AT GAY BARS AND THE STONEWALL UPRISING

The 1960s and preceding decades were not welcoming times for LGBTQ people; for example, solicitation of same sex relations was illegal in the City. For such reasons LGBTQ individuals frequented gay bars and clubs where they could openly socialize without worry. However, the New York State Liquor Authority penalized and shut down establishments that served alcohol to known or suspected LGBTQ people, arguing that the mere gathering of homosexuals was “disorderly.”

In response to activists’ efforts, authorities repealed these regulations in 1966, and LGBTQ patrons could be served alcohol. But engaging in gay behavior in public (holding hands, kissing, or dancing with someone of the same sex) was still illegal and many bars operated without liquor licenses.

In 1966, members of The Mattachine Society, a gay rights organization, staged a “sip-in” where they openly declared their sexuality in taverns, daring staff to turn them away, and suing places that did. The Commission on Human Rights ruled that gay individuals had the right to drink publicly in bars, and the NYPD temporarily reduced its raids.

As it happened, the Mafia saw profit in catering to shunned gay clientele, and by the mid-60s, the Genovese family controlled most Greenwich Village gay bars. In 1966 the family bought The Stonewall Inn, then a “straight” bar/restaurant, and the next year reopened it as a gay bar.

Stonewall quickly became an important Greenwich Village institution. It was large and relatively cheap to enter. It welcomed drag queens who often encountered a bitter reception at other gay bars. It was a nightly home for many runaways and homeless gay youths, who panhandled or shoplifted to afford the entry fee. And it was one of the only—if not the only—gay club left that allowed dancing.

Raids were still a fact of life, but usually NYPD cops would tip off Mafia-run bars, allowing owners to stash alcohol and hide other illegal activities.

STONEWALL HAPPENS

When the police raided Stonewall in the early hours of June 28, 1969, it came as a surprise — cops hadn’t tipped off anyone. Armed with a warrant, the NYPD entered the club, roughed up patrons, and arrested 13 people including employees and customers violating the state’s gender appropriate clothing statute (women officers took suspected cross dressing patrons into the bathroom to check their sex).

Fed up with constant NYPD harassment and social discrimination, angry patrons and neighborhood people refused to disperse. Hanging around outside the bar, the crowd became increasingly agitated as officers aggressively manhandled people. A cop hit a lesbian over the head and forced her into a police van — she shouted to onlookers to act and the crowd responded by throwing pennies, bottles, cobble stones, and other objects at the police. Within moments a full-blown uprising involving hundreds of people began. The protests, with sometimes thousands of people participating, continued for five more days, flaring up at one point after the Village Voice published its account of the uprising.

On the one year anniversary of the riots on June 28, 1970, thousands of NYers marched in Manhattan from the Stonewall Inn to Central Park in what was then called “Christopher Street Liberation Day,” America’s first gay pride parade. Its official chant was: “Say it loud, gay is proud.”

KNAPP COMMISSION (1970-1971)

In April 1970 Mayor John Lindsay appointed the Commission to Investigate Alleged Police Corruption, or the “Knapp Commission”, as it came to be known after its chairman Whitman Knapp. Created largely as a result of the publicity generated by charges of police corruption made by Patrolman Frank Serpico and Sergeant David Durk, the commission’s mandate was to investigate the extent of corruption within the NYPD. After hearing testimony by whistleblowers from within the department, dozens of witnesses, corrupt patrolmen, as well as countless victims of ongoing police shakedowns, the commission concluded that the NYPD was beset by widespread and “systematic corruption problems.”¹²⁰ It identified two classes of corrupt officers: “Grass Eaters”, who engaged in petty wrong- doing most often due to peer pressure from within the department; and “Meat Eaters”, who were guilty of aggressive, premeditated corruption for personal gain such as such as shaking down pimps and illicit drug dealers.

Mayor Lindsay appointed Patrick Murphy to “clean up” the NYPD, tasking the new commissioner with implementing proactive integrity checks, transferring senior personnel on a large scale, rotating critical jobs, ensuring sufficient funds to pay informants, and cracking down on citizen attempts at bribery. Concerns arose, though, when Serpico was shot in the face during a February 1971 arrest attempt at an apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Circumstances surrounding his shooting led many observers to suspect that he had been taken to the apartment by officers to be murdered on purpose.

Though no formal investigation was conducted into the shooting, both that Serpico’s calls for help were ignored and that his colleagues refused to make a “10-13” dispatch to police headquarters (which would have alerted them to the fact Serpico had been injured in the line of duty) stoked suspicions. The incident, in effect, cast a long shadow on the NYPD’s willingness to respond meaningfully to allegations from whistleblowers operating inside the department.

POLICING UNDER DINKINS

(1990-93) AND GIULIANI (1994-2001)

Coming to power during the height of the cocaine epidemic both in New York City and across the country, David Dinkins began his term as New York City’s first black Mayor on January 1, 1990. He pledged to usher in an era of “racial healing”, referring to the City’s unmatched demographic diversity as a “gorgeous mosaic.”¹²⁴ While his first year in office marked the peak of homicides in NYC at a rate of 2,245 cases in 1990, his term saw a turning point across all categories of violent crime, ending “...a 30-year upward spiral and initiating a trend of falling rates that continued to accelerate beyond his term.”

THE CITY HALL POLICE RIOT

At the same time Dinkins sought to quell concerns about public safety, he was also balancing calls from the City’s communities of color to press for enhanced oversight of the NYPD. The new Mayor proposed a bill reorganizing the leadership of the City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) from an agency board made up of both police officers and civilians to one run exclusively by civilians. The City’s police union, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (now called the Police Benevolent Association) vigorously opposed Dinkins’ plan. On September 16, 1992, a rally organized by the union at City Hall became violent as 4,000 off-duty police officers jumped over a series of barricades in an attempt to rush the building. According to The New York Times:

At 10:50 A.M., a few demonstrators chanting, “Take the hall! Take the hall!” flooded over the barriers and into the parking lot in front of City Hall, meeting no resistance from the police on guard. Cheering and screaming, thousands of others poured through from every side of the park and seethed up the hall steps. Some mounted automobiles and began a raucous demonstration, denting the cars. While the rowdier demonstrators refused to leave the City Hall area, most of the group crowded onto Murray Street between Church Street and Broadway, where they listened to sharply worded speeches from [PBA President] Phil Caruso, [future Mayor of New York City] Rudy Giuliani and, finally, Michael O'Keefe, the officer who had been recently cleared by a grand jury in the shooting death of a Dominican man in Washington Heights. Many officers flooded the bars along Murray Street and drank openly on the street during the speeches.”

The rioters’ actions escalated: bystanders and reporters from The New York Times were “violently assaulted by the mob as thousands of dollars in private property was destroyed in multiple acts of vandalism.”¹²⁷ Una Clarke, a City Council member, tried to enter the building, but an off-duty officer blocked her from crossing the street. She later said the white officer turned to another officer next to him and said, “There’s a n***** who says she’s a council member.”

As beer cans and broken bottles littered the streets and rioters were unable to enter City Hall, their attention turned to the Brooklyn Bridge nearby, where, “[a]t least one on-duty officer opened up the barricades.”¹²⁹ Officers openly drinking and carrying guns blocked traffic in both directions for approximately an hour. They were “jumping on the cars of trapped, terrified motorists.”

According to Laura Nahmias from New York Magazine: “[Norm] Steisel, then first deputy mayor of operations, heard officers chanting, “Dinkins gotta go!” and “The mayor’s on crack.” They carried signs bearing racist cartoon images of Mayor David Dinkins with humongous lips and nose and an Afro, including several calling the city’s first Black mayor a “washroom attendant.”

Jimmy Breslin, a columnist for Newsday who had been severely beaten during a 1991 disturbance in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, was a recipient of rioters’ vitriol. A police officer holding a beer can exclaimed “How did you like the n*****s beating you up in Crown Heights?”. Other off-duty officers joined in, screaming the same question in his direction. Officers referred to Dinkins as a “n***** inside City Hall” and the “n****** Mayor”, while Mary Pinkett, a Black City Councilwoman, “was trapped on the Brooklyn Bridge and had her car rocked back and forth by off-duty officers.”

MOLLEN COMMISSION

Many of the problems within the NYPD addressed by the Knapp Commission in the early 1970's became issues of concern again in the early 1990s, as a new corruption scandal surfaced. Officers from the 30th, 9th, 46th, 75th and 73rd precincts were caught selling drugs and beating suspects.¹³³ To address these allegations, Mayor Dinkins appointed a commission that was headed by Judge Milton Mollen. In 1994 (Rudy Giuliani's first year as the City's mayor), following hearings, the Commission issued its final report; it included accounts of officers who came forward to back up the claims that they had become a vigilante squad with financial motives. When asked if the people he acknowledged beating were suspects, Officer Bernie Cawley answered, "No. We'd just beat people in general.” Reportedly, Cawley said that he used his lead-loaded gloves, flashlight, and nightstick over 400 times just to “show who was in charge." He would intimidate victims interested in reporting his behavior by explaining the amount of time it would take to type out their complaint.

According to other testimony from an officer, some officers kept the guns that they seized from raids and used them as "throwaway" guns – planting the guns on suspects involved in questionable arrests or police shootings to make it look as if the victim was carrying a weapon.¹³⁶ Cawley concluded by saying, "They [residents] hate the police. You'd hate the police too if you lived there."

The Mollen Commission report, which was published in July 1994, depicted an internal accountability system that was flawed in most respects. The report described the connection between corruption and brutality, and urged a proposal to solve both problems.

“When connected to acts of corruption, brutality is at times a means to accomplish corrupt ends and at other times it is just a gratuitous appendage to a corrupt act....[C]ops have used or threatened to use brutality to intimidate their victims and protect themselves against the risk of complaints.¹³⁸ We found that officers who are corrupt are more likely to be brutal....”¹³⁹

“Officers also told us that it was not uncommon to see unnecessary force used to administer an officer's own brand of street justice: a nightstick to the ribs, a fist to the head, to demonstrate who was in charge of the crime- ridden streets they patrolled and to impose sanctions on those who "deserved it" as officers, not juries, determined. As was true of other forms of wrongdoing, some cops believe they are doing what is morally correct - though "technically unlawful" - when they beat someone who they believe is guilty and who they believe the criminal justice system will never punish.”

The Mollen Commission exposed how everyday brutality had corrupted relations between police officers and NYers. The report heard from officers who revealed they had poured ammonia on the face of a detainee held in a holding cell and another officer who threw garbage and boiling water on a person hiding in a dumbwaiter shaft. Allegedly, a third officer doctored an "escape rope" used by drug dealers so they would hit the ground if they used it; the same group of uniformed officers raided a brothel, terrorizing and raping the women inside.¹⁴¹ The commission revealed: "...[B]rutality, regardless of the motive, sometimes serves as a rite of passage to other forms of corruption and misconduct. Some officers told us that brutality was how they first crossed the line toward abandoning their integrity."¹⁴² In his testimony, Officer Michael Dowd stated, "[Brutality] is a form of acceptance. It's not just simply giving a beating. It's [sic] the other officers begin to accept you more."¹⁴³ Previously mentioned Officer Cawley, as well as Officer Dowd, recounted hundreds of their own acts of brutality, none of which drew complaints or reports from other officers.

The Mollen Commission noted that "As important as the possible extent of brutality, is the extent of brutality tolerance we found throughout the Department....[T]his tolerance, or willful blindness, extends to supervisors as well. This is because many supervisors share the perception that nothing is really wrong with a bit of unnecessary force and because they believe that this is the only way to fight crime today."¹⁴⁵ The Internal Affairs Division was equally corrupt and often made sensitive cases disappear, presenting officer’s personnel files as up to standard, despite their criminal behavior.

After the Mollen Commission report was released, then-Police Commissioner William Bratton made a statement asserting if officers behaved properly, he would back them absolutely, but if they used unnecessary force, "all bets are off."¹⁴⁶ However, when Walter Mack, a civilian deputy commissioner in charge of internal affairs, lobbied for an initiation of a special anti-brutality unit available twenty-four hours a day to look into allegations, and took a stance on police perjury, he was forced out of the department in 1995.¹⁴⁷

Professor James J. Fyfe, an expert on police abuse who studied the NYPD’s reform efforts, found that the Mollen Commission's findings and recommendations had “little, lasting positive effect.”¹⁴⁸ In 1998, there were many corrupt police raids that raised important questions about officer training and the aggressive actions of the Department. Allegedly, in one case, officers wrongly raided an apartment and harassed the people living there with racial epithets and dressing a man in woman's clothing before taking him to the police station. In another instance, officers handcuffed a partially dressed, 8 month pregnant woman; she was so terrified by the experience that she reportedly urinated; but the officers did not allow her to change clothes for two hours.

THE GIULIANI ERA

Rudy Giuliani appointed Bill Bratton to head the NYPD. Bratton was, and remains, a leading law enforcement proponent of broken windows policing, a strategy that targets low level offenses like disorderly conduct and petty larceny as a way to prevent more serious crimes like rape and manslaughter. While, as Bratton has acknowledged, no studies have ever proven that broken windows practices are effective in reducing crime or improving public safety, research has shown that the approach has had an undeniably harmful impact on low-income communities of color. The NYPD’s own numbers — for instance, arrest data consistently show over the years that 87-88% of misdemeanor arrests involve NYers of color — essentially support the criticism of police reform advocates that broken windows tactics target Black and Brown communities for minor offenses that have been virtually decriminalized in White areas.¹⁵⁰

What broken windows did provide the Giuliani Administration, however, was the means to use the NYPD to address the City’s serious homeless problem. The policing strategies adopted had, in reality, less of an impact on actual homelessness in the City than on its visibility in the short term. According to The New York Times:

“The police began rounding up the homeless in a series of Manhattan sweeps in the mid-1990's, and many either moved out of tourist areas and went to less patrolled places -- or faced arrest and court summonses for such public nuisance violations as impeding the flow of pedestrian traffic. Police officials said [...] that the homeless could be arrested on charges of disorderly conduct or trespassing.”

The Giuliani Administration was by no means alone in its failure to address the homelessness problem in New York City through sensible and humane policies. But its policy of “cleaning up” NYC’s homeless population by “arresting them, sticking them in underserved shelters, and axing their community programs” was not only cold hearted, it was also counterproductive. It served more to move the problem of homelessness to the outer boroughs than it did to actually address its larger, structural causes.

CASES OF POLICE VIOLENCE

Several tragic and dramatic incidents of excessive police violence against Black New Yorkers took place during the Giuliani years:

** The killing in the Bronx of 23-year old student Amadou Diallo at the hands of the police–shot 41 times in front of his apartment building after reaching into his pocket to show officers his wallet.

** The brutalization, rape, and sexual torture of Abner Louima by four NYPD officers in a bathroom at the 70th Precinct Station House in Brooklyn.

Some critics claimed that the lack of accountability among NYPD officers when interacting with Black and Brown New Yorkers reached new heights under the Giuliani Administration. Perhaps nowhere is this abuse and misuse of authority more acutely apparent than in the case of Patrick Dorismond. An unarmed security guard, Dorismond was shot and killed outside of a Manhattan bar after declining an undercover officer’s attempt to solicit illegal drugs. According to Liberation Magazine:

“As Patrick left the bar after midnight, some middle-aged men approached him trying to score some marijuana. Patrick politely told them he didn’t do drugs and asked them to keep it moving. They insisted that surely he knew where they could score. The situation escalated until Patrick’s voice rose, warning the troublemakers to get lost. The men were undercover NYPD officers instructed to ‘bring in the dope-peddling good-for-nothings.’ Patrick, a 26-year-old Haitian-American whose parents had immigrated to Brooklyn, fit the cops’ profile of a ‘good-for-nothing,’and they planned to fulfill their quota. Without identifying themselves, the cops attacked the security guard. When Patrick defended himself, two other back-up officers–called “ghosts”–intervened, shooting him in the chest, killing him instantly.”

Within hours of the shooting, Giuliani–who then was in the midst of a failing United States Senate campaign–ordered NYPD Commissioner Howard Safir to release Dorismond’s sealed juvenile record. The files showed that Dorismond had been arrested at thirteen years-old for an alleged burglary and assault before the charges were subsequently dropped. Giuliani justified the release by citing the public’s “right to know”, suggesting that Dorismond’s “pattern of behavior” had contributed to his death:

''People do act in conformity very often with their prior behavior,'' Mr. Giuliani said [...] during a television interview on "Fox News Sunday.'' The news media ''would not want a picture presented of an altar boy, when in fact, maybe it isn't an altar boy, it's some other situation that may justify, more closely, what the police officer did.”

In the months following the slaying, it came to light that Dorismond, in fact, had been an altar boy–at the same Catholic high school once attended by Giuliani himself, Bishop Loughlin in Brooklyn. Adding more insult and irony to injury, at the same time the NYPD was publicly commending Detective Vasquez–the officer who fired the fatal bullet–for his service to the community, Giuliani opted to omit mention of the undercover officer’s disciplinary history, which included “drawing his weapon during a bar fight that he was reportedly involved in while off-duty in February 1997.”

Although Vasquez and the three other officers involved were cleared of any criminal charges, Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau acknowledged in a statement that Dorismond had “engaged in no criminal activity and had no idea that the three men whom he confronted after they asked him for drugs were police officers.”

THE BLOOMBERG ADMINISTRATION (2002-2013)

NYPD SURVEILLANCE OF AMERICAN MUSLIMS